“Is running too white?” It may look so past the elite corral at a major marathon. It’s a provocative question and a tough one to to tackle in an in-depth manner. Doing so requires discussions around a multitude of issues including community safety, socioeconomic factors, cultural influence, and privilege.

I know I can start, however, with personal experience. As a first generation Canadian of Trinidadian descent and South Asian origin, I’m among those whose background places them at a higher risk of heart disease and Type II Diabetes along with those of African descent.

I also have the experience of witnessing in myself the radical changes running can bring, both mentally and physically. Finally, I have the privilege of being in the middle of a running boom with many leaders in my age group in a city that proudly proclaims itself as the most diverse in the world. I know then, with running’s wonders and with its current explosion, that we’re presented with a golden opportunity.

To at least scratch the surface, I talked to three leaders in the city to learn a bit about how they’re leveraging the running craze and their personal experience to foster more inclusivity in Toronto’s running community and broaden the reach of running’s benefits.

Justin Osei-Dwumoh and Moe Bsat are staples at Parkdale Roadrunners, a group that immediately stands out for, as Moe says, “having more minorities than white people.” Moe points out that there are so many Fillipinos they have their own sub group within Parkdale known as the Adobros.

Justin and Moe both acknowledge that, going back to their days as high school runners, distance running was and to some extent still is viewed as a “white guy thing,” which Justin partly puts down to representation. He jokes that a Canadian or American person of colour, “with a bunch of tattoos and a grill needs to win a big marathon and change things the way Tiger Woods did for golf.”

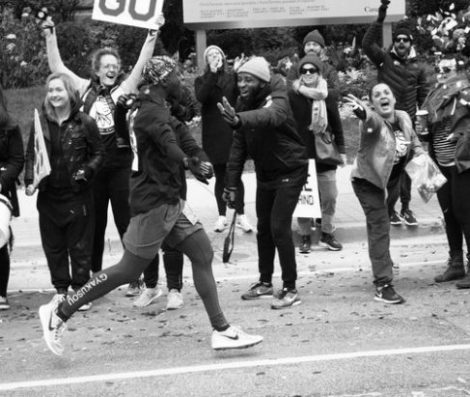

In a smaller but incredibly impactful way, this is precisely what Parkdale has accomplished with their social media presence. They’re not the sinewy Kenyans or clean cut collegiate runners that you’d typically see in running magazines. The vibrancy within the group strikes you immediately when they show up in your Instagram feed. That representation and the potential for someone intimidated by running with no previous connection to the sport to see a group where they feel they can be welcomed can’t be underestimated.

Justin, a former competitive basketball player, as was Moe, says that the cultural connection to distance running wasn’t present growing up (he’s Ghanian/Jamaican), and that may serve as a hindrance. He says, “A lot of guys who grew up playing basketball or football never transition out of it. They just keep chasing the dream. Even if they do transition out, it might be to crossfit or weight training so they still have that intensity. Distance running just isn’t a natural fit for them.”At Parkdale, leaders have used their personal experience to incorporate elements of sports and culture that resonate with members and that they recognize, creating something of a gateway for that transition. “You can say that we have kind of a street, hip-hop culture at Parkdale,” Moe says, adding, “We have the matching uniforms, the team spirit, and the social aspect where everyone lifts each other up.”

It’s Justin’s hope that the momentum they’ve built can help them take running more and more to youth in the city who will see it as something they can pursue that doesn’t necessarily require the seriousness of being an Olympian or chasing after Boston and where they can still have the social aspect of a team.

Khadijah Salawu is the founder of Run Regent, which runs out of the Regent Park area of Toronto. She founded the group with support from U for Change, which facilitates youth programming in the area, after noticing that the running boom didn’t seem to reach the neighbourhood in the same way that it did others in the city.

Much like the crew at Parkdale, Khadijah built Run Regent from the grassroots, engaging community members one by one to build something they felt they could be a part of. Khadijah posted flyers – not everyone is on social media, y’know – and attended community meetings to explain face to face what running could offer, namely the health benefits, which she feels can get lost in the image and the hype but which made running personal for those she met.

“We talk to people as much as we can,” Khadija says proudly. “Even when we’re out running, we stop and talk to people and explain what we’re about.” Taking this approach, those they engage see a less “commercial” and more approachable runner, one who looks like them and also happens to be enjoying it.

When they run, the philosophy is simple. No one left behind and support each other. No pressure to reach lofty goals. The group has been going for just under a year now and continues to grow having survived its first winter.

When we talk about diversity, what we’re really talking about is what Khadija refers to as equity. It’s not just a matter of being present in a community, but having a role in shaping it and the opportunity to draw from its riches. Toronto is certainly diverse and it’s running community is rich, but full participation is still lacking for many groups and in some areas of the city. The issues I noted at the beginning still loom large when it comes to determining the makeup of running. Through the proactive approach of the upcoming generation, however, change is happening.

In a sense, what Parkdale and Run Regent have done is not particularly groundbreaking. They simply listened to those they hoped to reach and began to reshape running in a way that made groups that weren’t typically involved in the sport feel they could belong. That’s equity and true inclusiveness. I’d like to think I did the same thing for my father.

I’d like to think, also, that these efforts will serve as a foundation for a long-term change. One thing that Khadija, Moe, Justin, and I share, with eight nationalities between us, is that we didn’t have parents or family members who ran. Should we ever become parents, our children will have parents who run. They will hopefully have the models of health that we didn’t. If the movement started by groups like Parkdale and Run Regent continues to build, the effects on the next generation can be powerful.

Current Issue

Current Issue Previous Issue

Previous Issue Prior Release

Prior Release